|

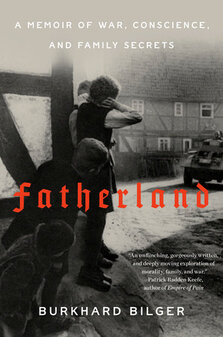

9/25/2023 0 Comments Burkhard Bilger's "Fatherland" This past April, I had just returned from a whirlwind (one week) trip to Switzerland and Germany with my brother and 89 year old mother when I learned the Burkhard Bilger had published a memoir, "Fatherland: A Memoir of War, Conscience, and Family Secrets." To say I was excited would be an understatement. Bilger's 2016 article in the New Yorker, "Where Germans Make Peace with Their Dead" rocked my world. I still remember precisely where I was -- in a hotel room in Poland (my maiden trip), overlooking the old Rathaus in the stare miasto (old town) -- when my daughter texted me, "Mom! You need to read this New Yorker article!" It gave a name to my weird German-American experience and set me on a journey of discovery that is ongoing to this day. And with "Fatherland," Bilger's timing once more was impeccable. My recently-completed trip happened to have taken me through the Black Forest region, a few kilometers from Herzogenweiler and wended westward to the small Badische city near the Rhine that is my Swiss grandfather's family's "Stamm Ort" or place of origin -- a place neither I nor my mother had ever visited, but which my brother was eager to show us. Whereas my genealogical curiosity tends to dwell on social history and speculating on family relationships, my ex-military brother has specialized in our family's military service history, and in this region and across the river into Alsace, France, he had done a deep dive into the WWI service of our grandfather, great grandfather, and various great grand uncles. As it happens, the first few chapters of Fatherland delve vividly into Bilger's grandfather's WWI service. His descriptions of deciphering Sütterlin military records from the Karlsruhe archives, of taking in the scope of and impact of that somewhat forgotten war (at least to Americans), felt deeply familiar. Again, the parallels were uncanny. So when I dove into Fatherland, it was with a profound sense of recognition. I could picture the insular Black Forest communities. I could hear Bilger's Alemannish, because it is so similar to my mother's St. Galler Schwiizerdütsch, a dialect that I understand but don't speak, which sounds like home. I had expected to connect to the book based on the German/paternal side of my story, his wrestling to make sense of a man and an identity when few clues remained, but for it to also, unexpectedly, connect with my maternal Swiss / German / Baden / Schwaben side just made it all the more special. Needless to say, I drank in the book. And the prose: Just. Gorgeous. It made part of me think, "Well, you might as well hang it up. There is no way anything you ever write is going to be even close to this good." Then, a small pang of jealousy. Would that I could quit my job today and just poke around archives and talk to people and write. Would that my own mother happened to have been a historian and written on World War II and its after effects. (Bilger's mother's thesis research centered on Vichy France.) Would that I could fortuitously stumble upon a municipal archive. Le sigh. But, as my daughter recently said to me, “You can do it too! You have a story! Just start" and I was touched by her support. We were headed to a snug German food hall (natürlich) after attending a book talk in Washington, DC between Bilger and his New Yorker colleague and old friend Atul Gawande, another one of those demi-gods who not only is an accomplished surgeon and public health official, but oh yes, finds time to write acclaimed essays and books on the side. The talk was a pleasure, another chance to feel seen, and more pleasurable still (beyond the later leberkäse sliders), it prompted some good conversation with my daughter about my upbringing and how it had impacted her and our family life. So here’s to more conversation, more connection. Prost. Fatherland, By Burkhard Bilger. Published by Penguin Random House. www.penguinrandomhouse.com/books/241123/fatherland-by-burkhard-bilger/ Sample Reviews

0 Comments

6/20/2022 0 Comments ParallelsOn February 23, 2022, we finally solved the mystery of what had happened to two of my father’s aunts, their husbands, and three cousins: They died sometime in the fall of 1944, in the Warsaw Rising.

On February 24, Russia invaded Ukraine. During the early days of the invasion of Ukraine, I was glued to Twitter, staying up until 1:00 am, 2:00 am, as if my obsessive doom scrolling could will the Ukrainian people through another night. I’m a news junkie, my work is in international relations, but this felt … different, more personal. Watching news reports coming from Kyiv, the fears of urban warfare to come, I could not help but think of Maria, Stefan, Tadeusz, and Łucja, of Marta and Danuta. For decades they were just names -- and only names -- in my big green “My Family History” book, jotted down at age sixteen when my Oma was still talking to me. Then six years ago, when my father died and never-before-seen old photos surfaced, I could add a cozy black and white group photo to the record. Seated in an intimate pyramid, seven adults at the back and five children in the foreground are crowded into what looks like a small living room: couch to the left, floor to ceiling lace curtains to the rear, a full-length mirror and patterned wallpaper looming on the right. Children are on laps, knees and arms touching. There are relaxed, natural smiles. For years, I stared and stared at this picture, not knowing who was who – other than Oma and the boys at the center – only that these were “the Poznan relatives," as the photo was marked, who had died, somehow, in the war, and simply vanished. Slowly, with the added benefit of online resources, I had been chipping away at this branch family tree. (Unlike so many armchair genealogists, who race to see how many generations and centuries back they can trace their family tree, I have plenty of basic mysteries much, much closer to home.) Then recently, a breakthrough. A connection with a distant cousin in Poland who not only spoke and wrote perfect English, who was born in Torun and living in Poznan, but who is as obsessed as I am about genealogy, and history, and resurrecting the lives of these ancestors. Cousin Anna, this kindred spirit, was more than willing to help me to solve some of my long standing riddles. And so together we made some rapid progress – a registry record, a birth certificate, a marriage record – until a search on the Warsaw Rising Museum’s new database of civilian victims of the Uprising revealed the long held secret. Maria, Stefan, Tadeusz, Łucja, Marta and Danuta had died during the fierce urban guerrilla fight for Poland’s capital. I now have a place and a timeframe. So it was with them in mind that I watched the news from Ukraine. My thoughts went still further back, 83 years ago to the German invasion of Poland. My father, a child of seven, evidently was among the crowds that welcomed the occupying Germans; by December my grandmother was working in the German civil service. Meanwhile some months later, the other half of the family would relocate to Warsaw, spending the war in the rump Polish sector. Much like news reports of divided Ukrainian and Russian families, I can imagine each side of my family not comprehending the choices and loyalties of the other. Finally, scenes of Ukrainian women and children thronging train stations and crammed into cars headed for the border and the unknown, dazed, unsure where they are headed, turn my mind to my own grandmother, father and uncle, bundling into a mail truck in the dead of night, in the bitter cold of January 1945, fleeing west ahead of the oncoming Russians. How exactly do you decide when to go? Is this the day, the night? Do you tell the loved ones you are leaving behind? What do you take? These are the things I think of when I scroll Twitter. They are not abstract questions. I know about this. Deep down, I know. |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed